I haven’t done this in 30 years.

It’s all muscle memory though, right? Once we get on it, everything will come back. Mek had looked me straight in the eye and asked if I knew how to ride a motorcycle.

‘Absolutely!’ I replied with utmost confidence, in spite of some inner doubts.

But that was 6 weeks ago, and on the other side of the planet. Now my hands are wrapped around the handlebars and a long ribbon of chaotic road is layed out before me. Did I mention they drive on the opposite side of the road here? Yeah, there’s that on top of it all.

The best thing I have going for me is a lifetime of urban driving in Montreal, one of North America’s most chaotic driving cities. I also have an experienced guide in Mek, who has run this route many times, but favors doing it at breakneck speed because life is short, and well, driving motorcycles fast is a rush.

The bikes are beat up rental Honda Supra X 125s, One twenty-five displacement is an average power plant for this part of the world. Judging from the hack marks around the ignition keyholes both vehicles haven’t always changed ownership through official channels. They came with only one helmet. We borrowed a second one for the week. They are also passed on with only fumes in the tank. This is standard practice in the region. Our first order of business is to fuel up.

We are on Nias, a 120 kilometer long outer island in the Indian ocean off the west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. We are headed to South Nias, 120 kilometers away, but haven’t even left Gunungsitoli in North Nias yet.

The bikes are ‘pass-through’ style, as it’s known in Australia, or a ‘bebek’ locally, which means ‘duck.’ A pass-through is a motorcycle body type that closely resembles that of a Vespa scooter with a footwell to store cargo. Mek suggests I put my backpack in the footwell. This will lower my center of gravity and make handling the bike much easier. The theory is sound, but I’ve never tried this before, and it’s an extra layer of complexity that I’m still not ready for. Mostly, I still need to look at my feet from time to time on gear changes, and the pack at my feet would block my view of the pedals.

Numerous times on the trip locals wondered why I didn’t store my bag in the footwell instead of on my back. They would point to my backpack and then to the empty space at my feet. Clearly this is the best way to move goods on a ‘bebek.’ I thank them for their suggestion, but continue to flout best practices. I need to practice this because Mek and millions of Indonesians are not wrong.

“You’re giving off a priest vibe,” Mek informs me.

Evidently, a slightly overweight, middle-aged white guy on a beat up motorcycle with a backpack is usually a priest in these parts. Indonesia is overwhelmingly Muslim, but Nias is over ninety percent Christian. Tourists usually have cars, but the modest priest travels by motorcycle. Two weeks earlier in Thailand I had a bean-shave, inadvertently wore an orange shirt and was frequently confused for a Buddhist monk. It wasn’t my intention to come to south east Asia to impersonate men of cloth but it’s working out that way.

“No worries,” says Mek. “There are far worse things to be mistaken for. Let’s roll!”

We are headed to a more remote part of an already remote island, specifically Sorake Bay, a competition-level surfing beach that could reasonably be described as the edge of the world. We aren’t going for the wave, but for the many hotels that cater to the surfers. From there we hope to visit the traditional village of Bawomataluo and the stone monoliths in the center of the island that are deeply meaningful to the island’s indiginous roots.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. We are still in town and since Nias is only a few kilometres north of the equator, the sun will set in less than two hours.

On the outskirts of the regional capital Gunungsitoli we pull into a gas station in mid-to-late afternoon on a humid Tuesday in July. After hopping off the bike a service station attendant is at the ready with a pump pistol. I don’t even know where the fill pipe is? She points the nozzle to the seat.

Right! It’s under the seat. Of course! But I have no idea how to get under the seat. Other riders are chuckling. ‘Bules’ (pronounced ‘boo-lay’) are a bit of a source of amusement here and I am certainly not disappointing the locals with my cluelessness at motorcycle basics. ‘Bule’ is a term used to describe light skinned people, invariably foreigners, that is not intended to be derogatory, but merely observational. It would be impossible to feel it as a slight, as many people in Southeast Asia are excited to see white people. They want selfies. They are genuinely pleased to meet me and can’t stop smiling or even laughing out loud for most of our encounters.

She motions at me to give her the key. The key! I oblige immediately and she slips it into a less than obvious keyhole above the rear wheel. The seat pops up an inch and lifts to magically reveal a storage area with a filler cap at the bottom. I strip the cap in an instant and the attendant assumes her filling duties.

I take the moment to nod and wave apologetically to the other riders who are chuckling at my expense. I have just wasted a half a minute of their lives, but nobody is holding it against me. More smiles. I pay cash with a sufficiently large bill to avoid further embarrassment.

Back on the road. We don’t get far when a hard rain begins to pound down on us. Water droplets are crashing into the asphalt with force. We take shelter in a closed business with a volunteer overhead roof.

The rain pounds the tin above. We are in the entrance of a fertilizer warehouse that is not particularly well secured but also doesn’t really offer a profound bounty to would-be thieves. I am grateful for the trust of the proprietors. A few other travellers have opted to wait out the downpour under the same roof. They are fascinated by Mek, a 6-foot four inch (193 cm) blonde ‘bule’ who somehow speaks fluent Indonesian.

Mek has spent the last 35 years in SE Asia. He is a fellow Canadian but has mostly left the north for what he finds a more resonable climate here. He has lived in a variety of countries but clearly favors Indonesia. This is not his first trip to Nias, but it’s been a while since his last visit, and he has assured me that this a magical island like no other.

In the moment, I’m in awe of rain being delivered by the sky in quantities not previously seen by this northerner. The corrugated steel roof amplifies the sound of the downpour that is holding us up. Despite the soaking, there is still a steady coterie of drivers unfazed by the wet conditions. Motorbikes, mini buses, cars and dump trucks all roll by albeit at a reduced speed. The rainfall ebbs and flows, at times feigning a finish before reloading for another onslaught.

When the rain clears, our roofmates get selfies with Mek and we go our seperate ways.

We’re off. We quickly clear the last of the roadside markets on the outskirts of Gunungsitoli and break into open countryside. It’s cooler now. The road is flat and straight for now, but mountains frame every background, so this won’t last.

The ‘motorcycle thing’ is rushing back. Shifting is familiar, but the rear brakes are lacking effectiveness. My comfort in riding and shifting gears is soon greatly overshadowed by the sheer activity level of a would-be rural road. This may be the countryside, but the road attracts people and businesses. What little population the area has is glued to the shoulder of the one main road of the island, for commerce, for survival.

A local pulls up next to me on the highway and points towards my feet. I take my eyes off the road to look down and see my kickstand is out. I have been driving since leaving the fertilizer warehouse with it dangerouly deployed. I kick it back in and thank him by nodding and smiling. He speeds off ahead and I am left wondering how long it might be before I stop making painfully obvious rookie motorcycle mistakes on this trip?

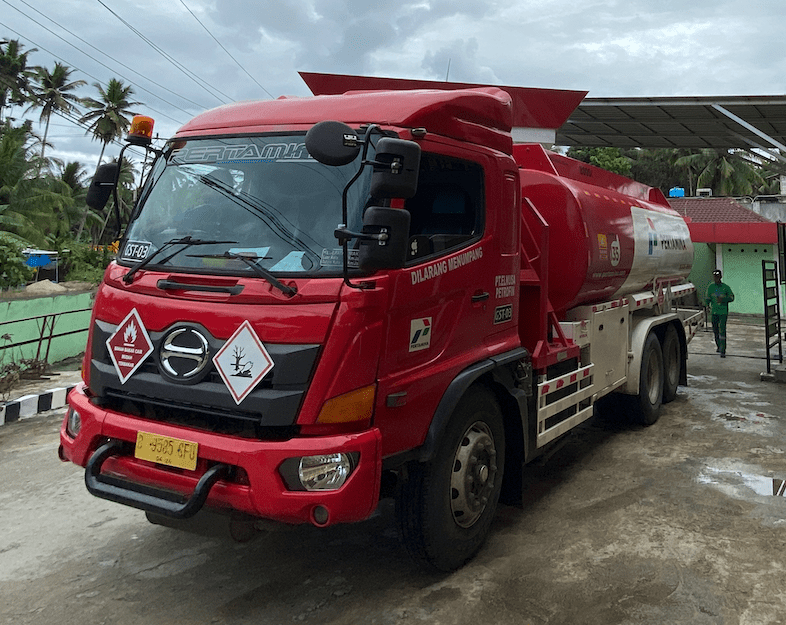

The single lane road is barely wide enough for two oncoming cars. The largest vehicles are the diesel tankers. These giant, colorful, logo-laden trucks take up their entire lane and half of the oncoming one, but there is a generous dirt shoulder which functions as a sidewalk or a place to pull off for an adjustment. The shoulder is flat, but full of puddles and loose rocks.

Before long the road starts to wend its way through a small mountain pass. There was little blasting done to route this highway, but rather a more practical methodology that seems to favor moving as little earth as possible and efficiently bowing to the mountain’s natural contours. The steepness of the grades and tightness of the corners varies greatly as result.

After the mountain pass is crossed and we return to another straight section through more farmland and rice fields.

Wooden racks of 2-litre alcohol bottles filled with diesel fuel dot the roadside. While towns and big intersections have official filling stations with pumps, these roadside businesses provide quick two, four or six litre top-ups for a slightly inflated price in return for their convenient location and lack of lineups.

Despite my desire to be alone on the road I find myself often driving in a pack of motorcycles created by a town delay or a hard to pass car. There is a a moment of chaos as a pack forms, but the group quickly self organizes into social hierarchies. Faster bikes float to the front near the centerline and slower bikes laden with passengers or cargo retreat to the back and remain near the shoulder. This happens effortlessly.

When a pack of motorcycles spots an oncoming fuel truck, the riders assume a single-file formation as quickly as possible. A few might attempt a last second pass, but mostly, everyone gets in the single file queue before the solid steel behemoth barrels through. The flat front of the tankers pushes a pocket of air that blasts the line of bikes, but this ‘de rigeur’ for these riders. As soon as the truck and its wake of oncoming traffic is cleared, the single file line widens again to its natural three motorcycle wide girth. Mek later points out that the tankers are all piloted by senior drivers with years of experience. Driving these beasts on narrow roads is not an entry level job.

Traffic moves at many different speeds, but we are among the quickest. We are passing everything in sight, even the cars which seem to proceed with more caution than one would expect. Only the full-sized motorcycles pass us on a rare occasion. They fly by at a considerable clip, but are all very safe and courteous.

The route to South Nias is a series of flat valleys and quick mountain passes. The weather changes as often as the terrain. Every pass and every valley has its own weather. Humidity is the only certainty. The passes are mostly rainy and cool. They are a break from the hot, humid rice fields of the flat valley floors.

There is a clear cadence to this highway. There are ‘passing moments’ when there is no oncoming traffic. When passing is not possible the bikes arrange themselves in preparation for the next opportunity. More eager drivers stay close to the centerline and hang close behind the vehicle they want to get by. Less eager passers hang back directly behind the obstruction or farther back on the centerline. More powerful bikes get priority.

Slower traffic keeps closer to the shoulder. I didn’t see any exceptions to this. Riders are disciplined. People afford extra space to an entire family sharing one bike and, in return, they don’t attempt much passing, preferring to putter along enjoying the scenery and staying out of the fray.

The worst vehicles to get caught behind are the yellow Mitsubishi Fuso dump trucks that are used for road maintenance. The high and wide bucket makes them hard to see past. They spew black diesel fumes that are detectible with every inhale. The yellow trucks seem to weave left and right more than other trucks and their tires kick up small rocks. It is advisable to get past them as soon as you can. Fortunately, they are usually operating locally and turn on and off the main road often, but the sheer number of them is an ongoing challenge.

A close second on the list of vehicles you don’t want to be behind older bikes with two-stroke motors. Once the default bike of Southeast Asia they are now relatively rare, largely replaced by more powerful and smoother four-strokes. Some locals prefer the superb 2-stroke power-to-weight ratio which makes for more nimble handling. Others like the ease of maintenance. Most 2-stroke riders are just extending the life of an old clunker out of economic necessity. Regardless, the bikes are distinctively loud and polluting. Follow a two-stroke for a mile or two and your face will be blackened by exhaust and your throat will hurt.

An important groundrule is to tap your horn when in the blindspot of a bike you are passing. This is especially true for cars and trucks, but motorbikes partake as well. It is a reassuring practice for both the passer and passee. I have never seen a vehicle horn effectively used for safety and not as a precursor to a shaking fist. I’m impressed with the friendliness of it all. It makes me want to pass people just to say ‘Hello!’

Drivers all over Southeast Asia are very courteous but are particularly so here in Nias. Motorcycles often join the road by a tactic North Americans would label as ‘cutting-off’ traffic, yet accommodating riders pouring in from side roads seems to be a fully accepted routine. Nobody is upset. Everybody adapts into a new equilibrium. The general idea is for all drivers to self-organize and survive cooperatively in real time.

I have not seen any road rage in Asia, despite being on the road near continuously for weeks. At home, I can’t go to the grocery store without seeing two motorists enraged at each other over a minor slight. The contrast in personal comportment is a chasm and I feel immediately won over to this more peaceful and tolerant approach. The sense of community here is light years more developed than the ‘me-first’ attitude in the west.

Even very young kids ply the highways on their way to their classrooms. Despite their youth, they remain disciplined pedestrians.

There are very few safety road signs. Sharp turns or hidden entrances are not marked. There is no complex line painting on the road surface to sort traffic into special turning lanes. There are no special turning lanes either.

I kind of appreciate the lack of signage. There is already enough going on that bright yellow diamond-shapes would only add more noise and distraction. A single sign every kilometer that says ‘STAY ALERT’ might be a strategy, but I think the locals are already keen to the ever present potential for instant chaos. And there is likely no budget.

Pedestrians are everywhere. The shoulder is frequented mostly by women and children. The women are sometimes carrying water or greens used as pig feed which grow well on the undeveloped portions of roadside between the jungle and the asphalt.

Twice a day the road is crowded with uniformed school children in vast numbers that suggest long walking commutes. Their bleached white shirts appear fantastically clean and bright and greatly elevate the road’s cache. Even very young kids ply the highways on their way to their classrooms. Despite their youth, they remain disciplined pedestrians. North American kids of the same age could never be trusted to walk this highway. I am impressed with the maturity of these youngsters while also worrying about their safety.

Finally, there are dogs and chickens. What they lack in numbers they make up for in sheer unpredictability. Some head directly towards the road and veer away at the last second. Others parallel the road then, without warning, dart into traffic and back out without apparent reason.

In Canada, a rural road such as this one would be an opportunity to zone out, throw on some tunes and enjoy the scenery with one or two fingers on the wheel. With so many houses, markets and farms perched on very edge of the shoulder that is not possible here. Riding this road is continuous exercise risk assessment. There are definitely moments of smooth road and little or no chance of collision which would permit your mind to drift to some of the other pressing topics in your life, but those moments are rare and taken at your peril.

Some villages are so attached to the highway that they celebrate weddings and similar gatherings on the road surface. A row of used motorcycle tires are lashed together with rope or chain and layed across the road to alert traffic to roll slow. The first tire line is a warning, the second outlines the party’s borders. All traffic comes to a crawl and files through the middle of the festivities. You can hear the karaoke (or simply live amateur singing, I can’t tell), send a quick smile and wave to the happy couple. In the middle of the party is a large billboard with vibrant colored plastic flowers that notes couple’s names, the date and the name of the village. A few seconds later you hit the tire line set for oncoming traffic and you’re off, shifting back up to full speed again.

The passes are a welcome break from the flat valleys. There is less traffic, less passing and, as nobody is living directly on the roadsides, less hazards. You are more free to relax, find your favorite riding line in the curves and soak in the mountain jungle scenery.

Behind every mountain pass is a river crossing. The traffic highway slows for these traverses if for no other reason than the steep ramparts to reach the bridge’s elevated platform height. The bridge is built on steep ramparts at either end that hints that the river is capable of rising very high.

The asphalt covered approaches to the bridges are rife with newly formed water-filled potholes. Older potholes have been hastily repaired with poured concrete. The motorcycles must all slow to first gear to climb the ramparts and navigate this minefield. The cars must take the hit. The large-wheeled trucks roll right through seemingly unconcerned.

The bridge surface itself is smooth and well maintained, but the traffic still moves slowly across the span because of the spectacle below. The waters are raging, roiling cauldrons of brown water racing a short but dramatic course from the mountains on the right toward the nearby sea on the left. A few motorbikes have stopped entirely to witness the mayhem. Apparently enough rain has fallen to make this scene mildly newsworthy even to locals. I would like to stop, but we are racing the setting sun.

Around halfway we need a break. We pull onto the shoulder and into a random business selling roadside refreshments. There is no shortage of them.

After parking our bikes, we hit our first snag. The key to my bike was gone. It had fallen out of the ignition somewhere on the road. I couldn’t turn the motor off. Mek immediately asked the shopkeeper for advice. He asked for the other key, the one to unlock the seat to which accesses the gas tank. The second key worked in the ignition and we shut off the bike. It seems the sordid origin story of these motorcycles meant that near any key on earth that could be slid into the keyhole was enough to turn on the ignition. It also means I have to start my bike and remember to remove the remaining key and stow it in my pocket to prevent from losing it.

A second issue immediately emerges. Mek cannot unlock his seat to check how much gas he has left. We determine that we got the keys mixed up when we departed Gunungsitoli (since any key starts my bike) and that the key that fell out on the road was likely the only one that unlocks Mek’s seat and tank access. Our bikes are the same model and since I had more than a half tank remaining, we assume Mek has the same. But the missing key is a brewing problem for the coming days.

Mek orders tea rolls himself a cigarette and, for me, he recommends a Japanese drink called Pocari Sweat, which is a, sort of, eastern version of Gatorade.

Before long there are children everwhere. They are full of curiosity. What are our names? Where are we from? Where are we going? Why does Mek speak Indonesian so well? Why do I take so many pictures? As usual, Mek draws the most attention. He is great with kids. He is patient and answers all their questions until they can’t think of any new ones. Once they are fully satisfied, they just stare at us. All of them wanted their pictures taken. I gladly obliged.

The roadside shop is built directly over a fresh-looking moutain stream and doubles as a bridge. A teenage girl tosses her empty plastic bottle over the railing and into the fast-moving stream directly below. She does so without a hint of hesitation or guilt.

Of all my personal encounters in Asia the most common inquiries I get are what drew me here, what do I like and what do I dislike? It is clear they are eager to become a Bali-like destination and are unsure of what local characteristics may be coming up short. I have never been to Bali, but I am nonetheless compelled to point out that the plastic litter is huge turn off to westerners.

The casual way plastic litter is discarded in southeast Asia is particularly shocking. While trying not to be too judgemental, I explain that the plastic litter shatters the illusion of paradise most western tourists seek when they voyage to the tropics. Universally, the message is understood. Locals know the litter is problematic, but it is a persistently hard problem to eradicate. Some areas don’t have any garbage collection service, meaning the most common way to dispose of plastic is to burn it. The collective site and smell of myriads of piles of burning plastic on a regular basis is not helping the tourist numbers.

On a more positive level, chemical pollution is seemingly non-existent in Nias. A few months before our arrival in Nias, a ship carrying raw asphalt ran aground off the north coast of the island and causing environmental damage effecting local fishermen. But for the most part, there are no abandoned open pit mines with huge tailings piles, no chemical residues of the industrial revolution that plague parts of the world that aren’t so remote. There is a dividend to missing out on the twentieth century’s factory festival, it’s an unspoiled landscape of lush jungle.

Environmental concerns in Nias are centered more around the stripping of resources. Sand is removed from beaches for concrete, and wood illegally harvested from the mountains. These are also hard problems to fix when poverty is ever-present and these resources are universally needed for shelter and prosperity.

Nias does have a lot going for it. A tourism boom in the near future is not out of the question. It is safe, friendly, beautiful, warm and has a rich cultural history that is well preserved. There are opportunities for eco-tourism, cultural explorations, trekking, surfing or just lounging on a beach. This process is just beginning.

Halfway there we stop to rest and get a cold drink. The area children are excited to see visitors.

It’s time to press on. Mek pays the bill, we wave goodbye to the children and promise to stop again on our return leg. The sun is lowering and losing intensity. It is late afternoon.

There are also towns along this route. Each has a very different vibe. The very center of one town seperates me from Mek. I was unable to pass a truck that he got by quickly. The road becomes so crowded with pedestrians that traffic comes to a crawl. The road is muddy in the center of town. It feels like I am driving in an open air market. People cross the road with impunity in town. They carry boxes, bags, propane cooking canisters and any other necessities of life. Nobody is upset with anyone else. Eveyone is patient and understanding of each other’s challenges. There is a sense of community and tolerance. I can imagine this chaotic situation devolving into arguments in the west, but here large crowds co-exist far more harmoniously.

Clearing the center of town I encounter a crossroads on the edge of a knoll. The road splits in two directions at what is either a small monument or a large mile marker. Many people are chilling on their bikes here, presumably waiting for someone in the market to be done with their errands.

Both roads out of town looked equal in size. This is the first time I have sensed an ambiguity in the main road south and, of course, this happens moments after I am seperated from Mek.

I join the crowds chilling all around the intersection and watch how much traffic uses each road. The first five vehicles go right. The next five vehicles go left. Time is wasting. I conclude that the left road stays close to the ocean, and if it doesn’t continue south it will end quickly at the coast. But the right road could lead into the island interior and continue for miles.

I start down the left road at speed, keeping my eyes peeled for Mek. After a minute or two Mek pulls along side me on the right.

“What happened?” he shouts over the road noise.

“Nothing, much, I just stopped in town to figure out which was the main road.” I reply.

“Then what happened?” he deadpans, implying my decision took a really long time. Considering we are racing against imminent nightfall, he is not wrong to point out the lost minutes.

I ask if I drove by without noticing him and he tells me I did. There is so much activity, even on the edge of town. One can drive right by someone you are searching for. Maybe I just lack practice?

Photo by Nitrasari Fau.

The sun is below the horizon now and whatever light remains is from a crimson sky that is squeezing the last rays of the passing day. I fumble for the headlight switch but no beam materializes. I start pressing any and all buttons I can feel and only the horn is functioning normally. A quick glance behind me reveals no red glow of a tail light either. I’m practically invisible to traffic approaching from behind. Rentals! At least the traffic is light now. We are the only ones still headed south that I can sense, but there remains considerable oncoming traffic.

Eventually Mek senses I am struggling and slows to match my speed.

“The headlights are for shit,” I yell. He nods like he half expected them to be out and instructs me to tailgate him and match his tire line… “exactly!”

I use his headlight as my own and split my attention between the lit road in front of his bike and his rear tire. It’s sketchy as hell but it works.

The trees start to form a tunnel enveloping the road. They intermittently block what little daylight remains. It’s a preview of the total darkness that is just minutes away. We are done with farmland. The road is gently winding through deep forest. I can smell the sea.

I remain fixated on Meks headlight beam as we barrel through the forest. I miss most of the potholes, but fully strike a few as well.

Hitting an unexpected pothole on a motorcycle can be extremely hazardous. The far side of the hole could wrest the handlebars from unprepared hands, and leave you in the ditch. A white knuckle grip doesn’t afford you the nimble control needed to guide the bike safely around the potholes. It’s a gamble either way and the chips on the table are bone fractures, road rash or worse.

A solid pothole strike sends an initial shockwave up your arms and into your shoulders, but the real earthquake a few milliseconds later starts in your lower back and moves up your spine in an instant and induces a mild whiplash of your helmet laden skull. After a moment of utter terror, a moment of joy overtakes you as you realize you’re still upright and rolling on.

The temperature is perfect. I am not hot anymore. My clothes, dampened by earlier rains, keep me nicely radiated from the equatorial heat. Despite the acute dangers of the moment, I am enjoying this!

Then, without warning, I saw it. The open ocean to the left. It is the edge of the world. The roaring waves lit in blue by the very last vestiges of daytime. It is not moonlight, but a striking cerulean blue of dying daylight casting equally on both ocean and sky. They only differ in texture, separated by an imperceptible horizon.

I can’t look away, even though taking my eyes off the road could easily bring me harm. I should be fixated on Mek’s rear tire, but my first glimpse of the Indian Ocean is the one the most magnificent landscapes I have ever seen.

The smashing waves echo through my helmet. I only hear them after the stunning visual before me is fully absorbed. The sound hits me a moment later. It’s loud. Large waves striking immovable coastal rock loud. This is surf country after all. People come here to ride ferocious beasts and it’s high tide. What visual paradise have I stumbled on? I never expected this treat. This bike trip had been something to endure but has quickly become a featured destination.

The blue of sky and water is deep and complex. The scene before me is both inviting and intimidating. It is a postcard with bite. Look. Enjoy. Don’t come closer.

I am experiencing a perfect blend of fear and ecstasy that is oddly reminiscent of a life well lived. A calm washes over me and I feel unrealistically invincible. What cruel god would interrupt such a perfect moment with life’s end? For a second or two, I am floating through the universe at peace with myself.

Sea spray begins to land on my glasses and cloud my vision. I return to my senses. I feel mortal again and in increasing danger. I can’t wipe them easily. If I stop on the shoulder Mek would never know. I am invisible in this darkness. He would drive on unknowingly and I would be left on the shoulder in the pitch dark of a new night, albeit with a spectacular view for at least a few more minutes.

I refocus on a now fuzzy rear wheel and do my best to pick out the potholes. This is sketchy as hell, but we are mostly alone. Oncoming headlights illuminate the accumulated droplets and blind me for a moment. We are not going fast anymore, but it feels precarious.

Mek’s bike begins to slow even further. He is scoping the surrounding terrain. Despite reservations we pull off the main road. We are headed towards the sea at a paltry 10 kilometers and hour while Mek scopes the surrounding terrain.

Our final destination is a hotel at the famous competitive surfing beach of Sorake. Mek has been here many times, but not recently. For the first time in days of travel together he is genuinely confused. His familiar landmarks have changed, and he is not sure where we are.

Advancing slowly, he is shaking his head. Evidently, a wave of development has overtaken Sorake and the result is less than pleasing to him. He has not been here in 6 years but assures me the changes are dramatic. Cheap credit flowed across the country, likely a good thing, but here in Sorake the resulting development seems unplanned and of substandard quality.

On the side road of the oncoming lane we see western tourists walking back to their hotels from dinner. The mood is quiet and chill. My eventful ride is nearing a conclusion, and I appear to have survived. We pull over and stop in front of a hotel that is clearly in full evening party mode.

This is Mek’s usual hotel in Sorake, but it has soared in popularity. It is now priced for tourists, and full. We settle for the adjacent neighboring hotel with only four rooms, which is still reasonably priced an has a pair of available rooms. The buidings share a wall and the party noises easily spill over.

For the next few days we would share the hotel with pair of surfers from the US, including William ‘Bill’ Finnegan, a writer from the New Yorker magazine and Aaron, an NGO representating his own charity trying to bring funding for water projects in remote local villages. The hotel owner was ‘Damon’, who’s legal name is Democracy.

All of us had immediate problems. Mek and I needed a motorcycle mechanic to unlock the seat before the bike ran out of gas. This is not usually a big problem, but little challenges can prove tough to resolve in remote areas. Damon was having issues with the hotel’s water pump. Aaron’s charitable efforts were being blocked by a local chief for reasons he couldn’t understand. But it was Bill’s challenge that intrigued me the most. Bill was at Sorake to score an interview with a local surfing legend. As one who formally studied journalism, I can appreciate any quest to secure a ‘must have’ interview.

It seems the 2004 earthquake raised the seafloor at Sorake and, as result, permanently altered the wave. Rumors in the surfing world were emerging that the new wave was not as good, but this experienced local was adamant the wave was different, but far from inferior. This is the kind of local knowledge and bona fide expert opinion that the global surfing community craves. It promised to be a great face-to-face. Only problem was, the legendary local surfer didn’t want to be interviewed.

The wave has both a left and right hand break. It is known for year-round consistency and for having an array of waves for different surf-skill levels. International competitions are held most years at Sorake. They take place at the discretion of competition organizers who are endlessly trying to predict where on the globe the best waves will be.

Looking out over the Indian Ocean from South Nias is like staring into deep space. There is nothing out there. To one’s right is the southern tip of India, a paltry 2,000 km away. Stare straight ahead and you are gazing towards Madagascar and the coast of Southwest Africa only 8,000 km away. And off to your left lies Antarctica, a mere 10,000 km, if you don’t count the pack ice limit. The Indian Ocean averages almost 4,000 metres in depth and has very few islands in its midst.

Behind you, only 100 km away, lies the largest of Indonesia’s 6,000 Islands: Sumatra (Sumatera locally, which means ‘Land of Gold’). Beyond that are all the great population centres of Eastern Asia.

We would spend the next few days enjoying good food, solving each other’s problems cooperatively, and lounging at the nearby beach at Lagundri. At the time Mek and I moved on from Sorake, Bill still had not secured his interview.

A week later at the airport in Gunungsitoli, we bumped into Bill again. We were all leaving Nias albeit too soon.

“Did you get your interview?” I asked.

“I did!” he replied with a small look of satisfaction mixed with exhaustion.

Another satisfied customer returning from the edge of the world.