January 15th, 2024

I’m usually pretty decisive. This time, not so much.

There are thousands of decisions to make when planning an Appalachian Trail thru-hike. The direction you hike probably shouldn’t be a difficult one, but for me, it is.

The choices are pretty straightforward: head northbound (NOBO), head southbound (SOBO) or combine them both in whichever way you want, but still finish the entire trail in a year (Flip-flop). For the hardcore, you can do the whole trail in both directions in a year (Yo-yo) which may simplify the ‘direction’ decision, while complicating almost everything else by doubling the overall mileage.

For me, souhthbound (SOBO) is pretty much out. Starting with 5,269 ft. (1,606m) Mt. Katahdin and following immediately by the 100-Mile Wilderness is the stuff of younger hikers who haven’t yet had the pleasure of working in an office for a few consecutive decades. But mostly, being over 50 a slow start building to a crescendo is a far more appealing cadence than doing 80 per cent of the difficulty in the first 20 per cent of the distance.

Hiking Katahdin first is a cold bore shot bound to miss the target by a wide margin. This feat would be immediately followed by the hundred mile wilderness. To say the southbound AT experience lacks foreplay is an understatement. As soon as the gates open, hikers meet advanced conditions of all stripes: swollen spring river fords, bugs, high mountains, muddy trail conditions, and difficult re-supply. Maine is no place to hike with training wheels attached to your ankles. I need to start slow and let my trail legs gather underneath me.

On a superstitious note, ‘going south’ is a common American expression for failure. Whether its origin is in heading to Mexico for refuge, a nod to an unfavorable drop in the stock market, or just the orientation of most maps having south at the bottom, the literary side of me doesn’t want to tempt fate.

If I left northbound (NOBO) in mid-February, I might reasonably be in Hot Springs, NC when AT March Madness* kicks off and hoardes of twenty-something hikers set-off daily from Springer.

But there are other benefits of jumping the gun. If I’m quick, I might reach the coolness of the Green Mountains of Vermont before the intense heat of summer begins to sear the lowlands from Front Royal to the base of Mt. Greylock, Massachusetts. Bug season, while unavoidable, might also be slightly shortened by my earlier start.

Historically, hikers don’t leave en masse until March 1, with March 15 being the peak departure day. By this time, the southern spring is in full form. And while late winter storms are still possible, the average daily temperature is getting quite mild and enjoyable for distance hiking.

Leaving mid-February will expose me 2-3 weeks of colder daily temperatures (more importantly, nighttime temperatures), but nothing that would cause a lifelong Canadian any major discomfort. The trip south to the Springer mountain southern terminus will likely shorten my winter experience considerably, since Canada is in a different league of winter chill than Georgia.

Leaving early also limits my top speed. If I hiked a 4-month pace from a mid-February departure I may get held up by unmelted snow on mountain peaks in Vermont and New Hampshire. Snow on the highest peaks in the north doesn’t fully melt until late May or early June. By hiking at a reasonable 5-month pace I will reach these mountains in fresh crisp late spring form.

But most importantly, the full northbound experience is what I have pictured in my mind’s eye for a decade or more. There are some sections and views that I never pictured doing in reverse. The spectaclar descents to the N.O.C. and Erwin and crossing the Fontana Dam before ascending into the Smokies are only a few of them.

It is the classic experience. Although not the one originally envisioned by the trails creators, who felt a southbound direction made more sense. AT thru-hiker number one Earl V. Shaffer went northbound in his groundbreaking 1948 hike, and according to ‘The Trek,’ changed the default experience forever “whether we realize it or not.”

There is also the idea of one long continuous journey in one direction and headed home. It evokes feelings of Homer’s Iliad or dropping a possessed ring into lava after crossing Middle Earth.

Finishing on the peak Mt. Katahdin, Maine (the northern terminus) is an epic location for that final trail photo. And if I were to reach the northern terminus, my house is a only a few hours drive away.

Lastly, a continuous hike in a single direction makes it easier for friends and family to track my progress, without the confusion created by bouncing to different locations and walking in opposite directions.

NOBO was what I always dreamed of, but the foundations underneath this certainty are cracking.

A few events have begun to change my thinking though. The first was watching Craig ‘Hawk’ Mains 2020 videos of a flip-flop hike. The fall landscapes were beautiful. The southern section in fall is more lush, and more photogenic. It seemed to far exceed the spring experienced by northbound hikers in ‘stick’ season, with the only drawback being reduced views because of trees fully laden with leaves. (The Appalachian Trail nickname: ‘the green tunnel’ is well-earned.)

Craig started in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia (the unofficial midpoint of the AT) in midsummer and trekked north with the surviving northbounders after the year’s hiker bubble had suffered the majority of its inevitable attrition. He continued north and reached the northern terminus in late summer, only to return to Harper’s Ferry and begin southbound to Springer Mountain, Georgia. A quick hiker could finish in late October or early November, beating the bite of winter in the Smokey Mountains roughly 200 miles before the finish.

The midpoint flip-flop is highly encouraged by the AT Conservancy as a way of better distributing trail resources and lightening the March bubble in Georgia. Increased popularity means you won’t hike the southern section alone with your thoughts. Many trail families are posting moments of camaraderie on social media as they wend their way through the southern section in autumn. The trees have leaves. Kodak moments abound.

The second event undermining the NOBO is the ever-swelling numbers of northbound hikers following Covid. Anecdotal reports are that their are increasing numbers of thru-hikers on trail post-covid, with many leaving earlier as well. My bubble-busting plan was to leave early northbound and let the bubble catch me later when its size has thinned out. How far that might be is impossible to say. The average daily progress of an AT thru-hiker is about 13.8 miles a day according to the latest ‘The Trek’ AT hiker survey. While I hope to meet or even exceed that daily average, it may be difficult in winter conditions. But the increased numbers may place me at the beginning of the newer, longer peak season, instead of 2 weeks ahead of it.

And the last, unforseeable, event was a bout of persistent plantar fasciitis on my left foot that has plagued me since spring of 2023. Despite physical therapy my foot was not healing, until I had a ‘eureka’ moment. The source of the pain was my car. Pressing the car’s stiff clutch was pumping up my calf muscle and undoing my work to stretch it out. Engaging and disengaging a clutch repeatedly in a traffic jam places a huge load on the calf muscle, and I spent a lot of 2023 in traffic. The calf muscle is directly connected to the much smaller plantar muscle. Overworking the calf muscles causes them to contract and pull hard on the plantar causing a dull but persistant pain that doesn’t go away and will flare up considerably on long walks.

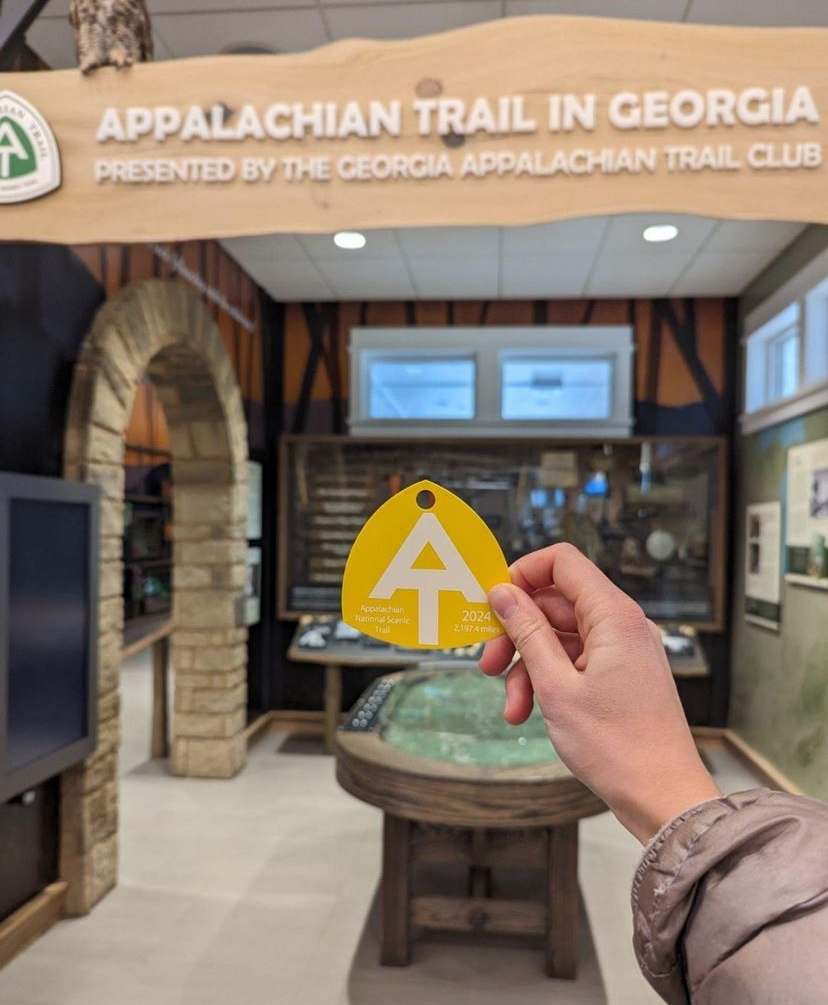

(Photo courtesy of AT Conservancy)

Within a week, I replaced my car with an automatic and let the healing begin! Progress has been slow and steady. While the pain has mostly subsided, I’m not sure it wouldn’t immediately flare up at the prospect of 15 miles-a-day of mountain hiking with the added weight of a backpack.

My reservation is for February 15, 2024 to leave from Springer Mountain, Georgia headed north. I will need to assess the feasibility of this on February 1, 2024 and make a firm decision then. If I am not confident of success, the flip-flop option (Plan B) becomes my best bet for a complete thru-hike in 2024. Waiting would afford two me two and a half more months to rehab my foot. Stay tuned!

* Don’t sue me NCAA

————————

February 02, 2024

The decision was made to postpone until April 9, 2024 to allow full healing of my plantar fasciitis issue.

The new ‘Plan B’ is to leave from the Springer mountain, Georgia southern terminus headed northbound. This start is quite late for a northbound hike, and will require a 15 mile (24 km) per day pace to reach the northern terminus before September 1st, and the cold fall weather starts to build in Maine.

Should I feel myself falling short of this pace, I will ‘leap frog’ north at McAfee Knob, Va (near Roanoke) at around Mile 712 of the trail counting northbound. I will take a bus to New York City and from there board a commuter train which will drop me directly on the trail at a tiny station named ‘Appalachian Trail,’ roughly Mile 1449 counting northbound.

By doing this I will have skipped the middle third of the trail and would find myself roughly where I would have been had I left on my original departure date of February 15, 2024.

I would then hike north to Mt Katahdin and summit sometime in mid-July. To complete the middle third I skipped I would have to go back to New York City again, take that same commuter train back the same Appalachian Trail station, but this time hike southbound back towards McAfee Knob, completing all 2,197 miles (3,536 kms) around October 4th, 2024.

The important thing is to hike the northern third in reasonably warm weather.

To boil it all down, it means I could save myself a lot of hassle moving internally in the USA by hiking 16-17 mile (25-27 km) days in the southern section and put myself in position to complete the hike in five months instead of six.

Plan C would be the aforementioned flip-flop: leaving Harper’s Ferry, WV in early May and hiking north to Katahdin, then returning to Harper’s Ferry to hike souhbound to Georgia in fall colors. The finish would be mid-November.

————————

February 25th, 2024

The decision is made to proceed with Plan B. I feel my left foot is sufficiently pain free to be able to support a 15-mile-a-day walking habit.

I am excited. I am relieved to be doing the southern section in a northerly direction. The AT Conservancy has accepted my modified departure date.

My mind is drifting back to some responses from successful thru-hikers, to the simple question: “What is the hardest part of hiking the trail?”

“Getting to the starting line,” was the surprising assertion.

It seems hiking the trail is much easier than putting your life on hold and presenting yourself at the starting line with enough cash and time off work and family to take those first steps. When I first read this I was a bit perplexed, but the statement never left my memory.

As I near the start line myself, I can safely say that getting there has been an epic journey in itself in every way. I cannot yet compare this challenge to walking 2,200 miles, but I am no longer confused by the surprise response to the question. Maybe the hardest part of hiking the entirety of the Appalachian trail is almost behind me?

Copyright © 2024 All rights reserved